Quick Read

- Grant Batty, legendary All Blacks winger and coach, passed away at 74 in January 2026.

- Known as a ‘pocket rocket,’ Batty (1.66m, 65kg) defied conventions, emphasizing skill over size.

- He scored 45 tries in 56 games for the All Blacks, including a famous intercept try against the British Lions in 1977.

- After retiring at 25 due to injury, he became a successful coach in Australia and Japan, guiding Easts to a premiership in 1997.

- Batty’s philosophy championed team spirit and simple mottos like ‘talk, tackle and keep the ball,’ influencing generations of players.

The rugby world is collectively mourning the passing of Grant Batty, an All Blacks legend whose impact transcended national borders and decades. Batty, who was 74, earned cult hero status during his playing days in the 1970s and continued to shape the sport as a revered coach across New Zealand and Australia for more than 40 years.

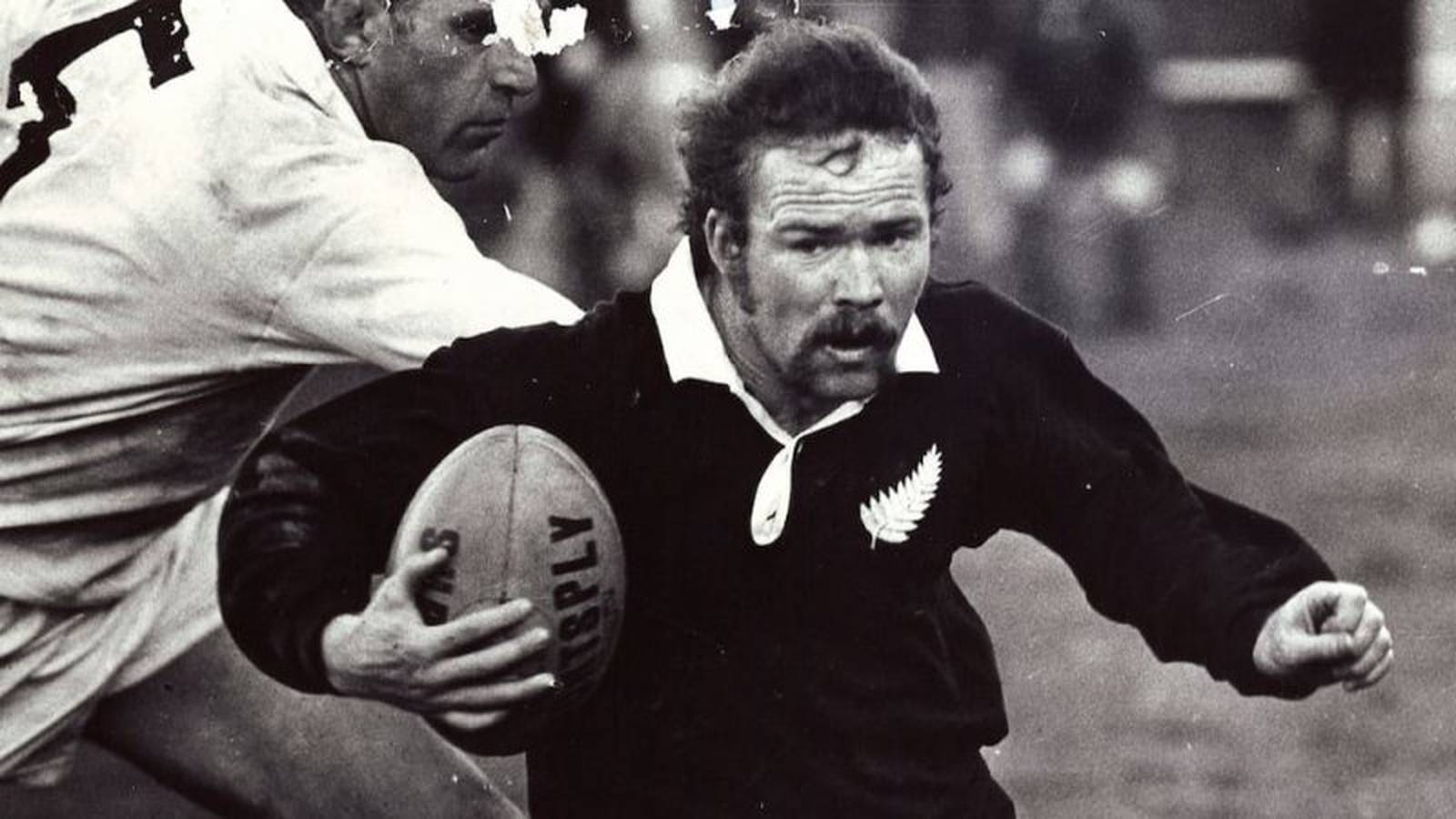

Known for his prominent moustache, electrifying speed, and a defiant approach that earned him the nickname ‘pocket rocket,’ Batty stood at a modest 1.66m (5 foot 5 ½ inches) and weighed around 65kg. Yet, he consistently proved that sheer size was no match for skill and heart on the rugby field. This philosophy became a hallmark of his career, both as a player who scored 45 tries in 56 games for the All Blacks (including tour matches) and as a coach who nurtured talent regardless of physique.

A ‘Pocket Rocket’ on the Field: Batty’s All Blacks Legacy

Grant Batty’s playing career, though relatively brief, was nothing short of spectacular. He played 15 Tests for the All Blacks, leaving an indelible mark with his fearless style and uncanny ability to find the try line. His commitment to the game was so profound that even a significant knee injury couldn’t immediately deter him from answering the call of his nation.

One of his most iconic moments came in 1977 during a memorable clash against the British and Irish Lions at Wellington’s Athletic Park. Despite battling a lingering knee injury that left him in considerable pain, Batty famously clinched the First Test with a breathtaking intercept try from halfway. He had initially declared himself unavailable for the match, but a persuasive call from teammates and coach Jack Gleeson convinced him otherwise. Reflecting on that pivotal decision, Batty later recounted to Qld Rugby, ‘I’d actually said I was not available for the First Test but a couple of teammates and the coach (Jack Gleeson) got on the phone.’ The roar of the home crowd as he crossed the line was a testament to his enduring popularity and fighting spirit.

However, the toll of the injury, coupled with the modest remuneration for All Blacks players at the time – a princely sum of $1.50 a day – led to a difficult decision. With his first child, Jane, newly born, Batty chose to retire from international rugby at the age of 25. ‘Driving back from Wellington to home, I worked out the knee wasn’t up to it,’ he explained. ‘I didn’t want to be caught out for a lack of pace or let down the All Blacks.’ Despite the premature end to his international playing days, he looked back with pride: ‘Forty-five tries for the All Blacks…not bad for a short-arse from Greytown. I’d had a great run and enjoyed it immensely.’

New Zealand Rugby acting chief executive Steve Lancaster described Batty as a ‘highly skilled player of his era,’ a sentiment echoed by Tony Giles, chief executive of Wellington Rugby, who called him a ‘massive part’ of the Wellington Rugby organisation. ‘He made so many Wellingtonians proud, and we know that the Marist St Pats community will particularly feel his loss,’ Giles added, as reported by News.az.

From Player to Mentor: Batty’s Coaching Odyssey

After hanging up his boots, Batty transitioned seamlessly into coaching, proving that his understanding of rugby extended far beyond his own on-field heroics. Moving to Australia in the late 1980s, he embarked on a remarkable coaching odyssey that saw him leave an indelible mark on numerous clubs and development pathways.

His coaching journey included stints with the Maroochydore Swans and a significant role in guiding Easts to their first premiership in 1997 as head coach. He also transformed the Gold Coast Breakers into Queensland’s top club side. Batty’s influence extended to higher echelons, serving as an assistant coach for the Queensland Reds in 1999-2000 and later coaching the Australia Under-19s in 2001. His expertise even took him to Japan’s Top League, showcasing his international appeal as a rugby mind.

Even in his 60s, Batty’s passion for the game remained undimmed. He resurfaced to coach the Quirindi Lions Rugby Club in 2014, a proud bush club in northern NSW, where he and his wife Jill had become locals in the tiny village of Wallabadar. This commitment to grassroots rugby, far from the bright lights, underscored his profound love for the sport and its community.

Batty’s coaching philosophy was refreshingly simple yet profoundly effective. He built successful teams on a foundation of strong team spirit and straightforward mottos like ‘talk, tackle and keep the ball.’ His special bond with the 1997 Easts team was evident when he made a rare return for their 25-year premiership reunion in 2022. He told Qld Rugby, ‘It’s more than the game itself, it’s the players and people you meet along the way that make rugby for me.’ He admired the diverse capabilities and body shapes rugby embraced, noting, ‘You can have a big, strong lock like Peter Murdoch, a skinny, fast winger like Ricky Nalatu and others like Andrew Scotney, who was an exceptional distributor and clear thinker.’

A Visionary’s Wisdom: Skill Over Stature

Throughout his career, Batty remained a staunch advocate for skill and strategic thinking over brute force. He believed that successful coaches were ‘primarily good selectors getting the right people in the right positions and having them believe in what you say.’ This ethos was evident in his admiration for modern players like Damian McKenzie, who, despite his smaller stature, excites fans with ‘speed, elusiveness, space and something special.’

Batty often lamented the changes in rugby that he felt diminished the role of smaller, agile players, particularly the increase in replacements that could negate fatigue. Yet, his core belief never wavered: ‘I never have or will think that rugby prowess equates to body size.’ This was not just a personal belief but a principle he embodied throughout his life, inspiring countless players and coaches to look beyond conventional wisdom and embrace the diverse talents that make rugby a truly unique sport.

His wit and rumbling chuckle, as remembered in his last major interview in 2021, were as trademark as his on-field exploits. From his humble beginnings in Greytown, New Zealand, to his significant contributions across the Tasman, Grant Batty’s journey was a testament to passion, resilience, and an unwavering belief in the spirit of rugby. His passing leaves a void, but his legacy as a ‘pocket rocket’ who reshaped perceptions of greatness will undoubtedly endure.

Grant Batty’s life was a masterclass in proving that the greatest impact often comes from the most unexpected packages. His career, both as a player and a coach, consistently challenged the prevailing notion that physical size dictates success in rugby, instead championing skill, intelligence, and an indomitable spirit. This dedication to the true essence of the game ensured his legend would resonate far beyond the touchlines, inspiring generations to come.