Quick Read

- Massachusetts’ minimum wage remains $15/hour in 2026, with a bill (S.1349) proposing a gradual increase to $20/hour by 2030.

- New Jersey’s minimum wage automatically rose to $15.92/hour in 2026 due to cost-of-living adjustments, with exceptions for some worker groups.

- Michigan’s minimum wage increased to $13.73/hour in 2026, following a legislative compromise after a court battle, aiming for $15 by 2027.

- Most New England states saw minimum wage increases in 2026 (e.g., CT to $16.94, RI to $16), but the federal minimum wage remains $7.25/hour since 2009.

- Social Security benefits received a 2.8% COLA for 2026, increasing average monthly payments by $55, but concerns persist about its adequacy against rising living and healthcare costs.

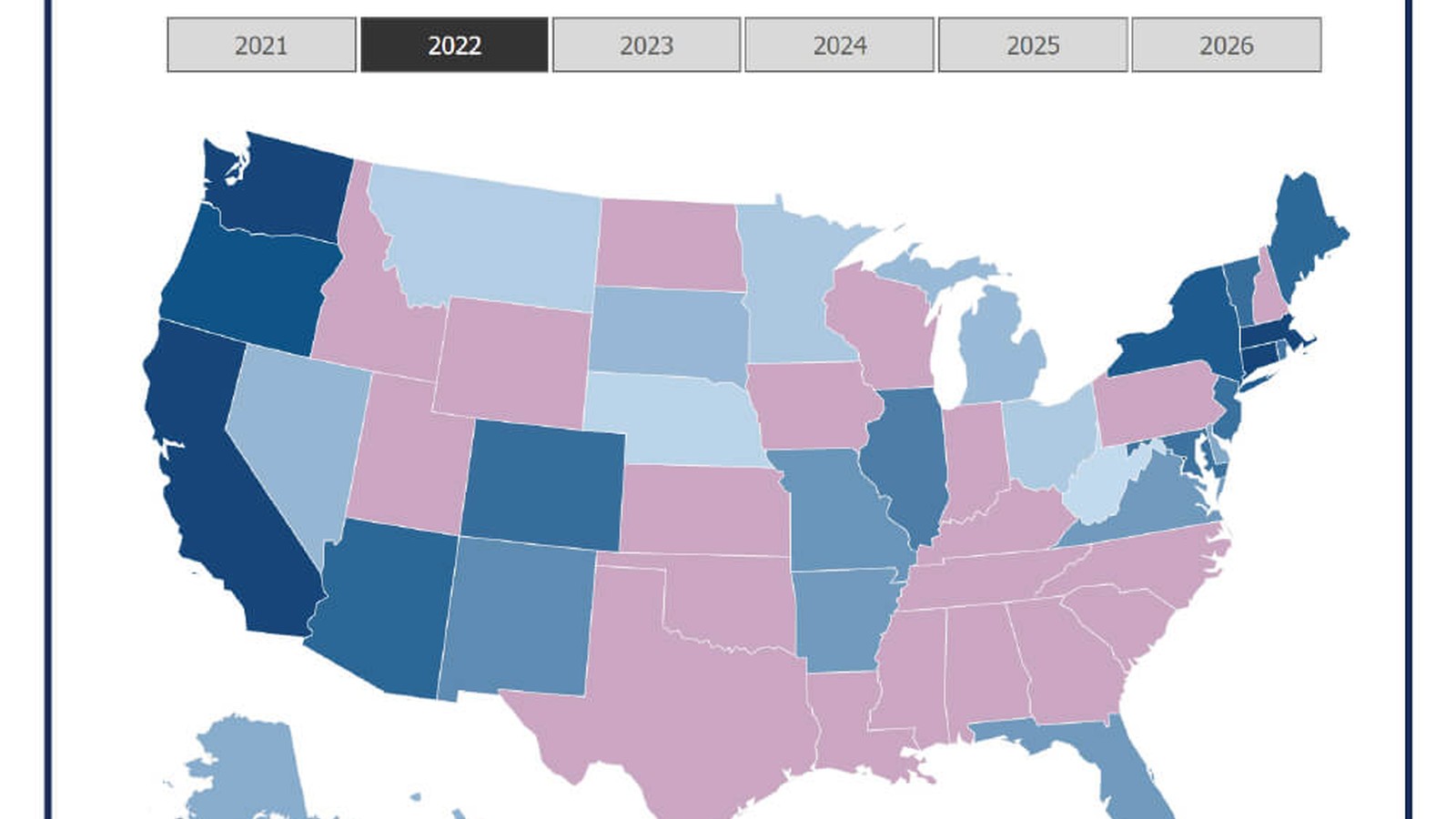

As the calendar turns to 2026, the economic reality for millions of American workers is a complex tapestry woven from disparate state policies and a stubbornly stagnant federal minimum wage. While some states have proactively raised their minimum hourly rates, often through automatic cost-of-living adjustments, others find themselves in legislative limbo, highlighting a national debate over fair compensation in an era of persistent inflation. This year underscores a widening gap between states committed to boosting workers’ purchasing power and those where the floor for wages remains unchanged, a stark reminder of the challenges in keeping pace with the rising cost of living.

Massachusetts’ Ongoing Fight for a Living Wage

Massachusetts, a state often at the forefront of progressive policies, surprisingly began 2026 without an immediate increase to its minimum wage, which has held steady at $15 per hour since January 1, 2023. This places it behind several New England neighbors, including Maine and Rhode Island, which saw their minimum wages surpass Massachusetts’s rate this year. The Bay State now ranks as the fourth highest in New England and 13th nationally, a significant slip from its previous standing.

However, the fight for higher wages is far from over on Beacon Hill. A bill, S.1349, remains active, proposing a gradual increase from $15 to at least $20 an hour by 2030. State Senator Jason Lewis, D-Winchester, the bill’s sponsor, emphasized the urgency, stating, “Increasing the minimum wage to $15 per hour has had a tremendously positive impact… However, due to high inflation, the buying power of $15 has been significantly eroded, and it is estimated by the MIT Living Wage Calculator that a single person living in the Greater Boston area would need to earn more than $30 per hour just to cover the basic necessities of life.”

The proposed legislation outlines a clear path for increases:

- 2026: $16.25

- 2027: $17.50

- 2028: $18.75

- 2029: $20.00

Beyond 2029, the bill stipulates that the Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development would implement annual adjustments based on the Consumer Price Index, mirroring practices in states like Connecticut, Maine, and Vermont. This long-term strategy aims to ensure wages continue to adapt to economic shifts.

The bill also addresses the tipped minimum wage, currently $6.75 per hour in Massachusetts. Under S.1349, this would also see a significant boost:

- 2026: $7.92

- 2027: $9.19

- 2028: $10.55

- 2029: $12.00

By 2030, the tipped minimum wage would be set at 60 percent of the standard minimum wage, with employers remaining responsible for ensuring total earnings (cash wage plus tips) meet the full minimum wage. Despite its clear objectives, the bill faces legislative hurdles. It is currently under review by the Joint Committee on Labor and Workforce Development, which has requested an extension until March 3, 2026. If it receives a favorable report, it will then move to the Senate Committee on Ways and Means. Given that the bill’s initial effective date for wage increases, January 1, 2026, has already passed, amendments will be necessary before it can become law, as reported by Telegram.com.

New Jersey’s Indexed Approach to Wage Growth

In contrast to Massachusetts’ legislative delays, New Jersey workers saw an automatic increase in their minimum wage on January 1, 2026. The rate rose by 43 cents an hour to $15.92, a direct result of a state constitutional mandate requiring annual cost-of-living adjustments. This mechanism ensures that New Jersey’s minimum wage keeps pace with inflation, based on changes to the federal government’s consumer price index. This automatic adjustment system positions New Jersey among more than a dozen states with similar indexing rules, according to Business for a Fair Minimum Wage, a national organization tracking wage policy.

New Jersey’s proactive stance is lauded by advocates for low-income residents, particularly in a high-cost state. Mitch Cahn, owner of Unionwear, a Newark-based manufacturer, highlighted the economic benefits, telling NJ Spotlight News, “Higher wages strengthen the economy – workers have more buying power and businesses see more consumer demand.” He added, “When you invest in your employees, you keep experienced employees who are more skilled, efficient and resourceful.”

However, not all hourly workers in New Jersey received the $15.92 rate. State law, championed by Governor Phil Murphy, includes exceptions for several groups of workers on a slower ramp-up to the $15 threshold. These include farmworkers, employees of seasonal businesses, and small businesses. For these groups, the minimum wage also increased, albeit to different levels: $15.23 for seasonal and small business employees (up from $14.53), and $14.20 for agricultural workers (up from $13.40). Tipped workers also saw their minimum cash wage rise to $6.05 per hour from $5.62. Additionally, direct care staff at long-term care facilities received a 43-cent increase, bringing their minimum hourly wage to $18.92.

Michigan’s Hard-Fought Wage Increases

Michigan’s journey to increased minimum wages in 2026 was marked by a significant legal and legislative battle. On January 1, the standard minimum wage climbed from $12.48 to $13.73 an hour, with plans to reach $15 by 2027 and then be tied to inflation. The sub-minimum wage for tipped workers also increased to $5.49, a figure that resulted from a compromise after a court-ordered schedule had planned for a higher rate of $7.97 and a full phase-out of the lower tipped wage. Minors, earning 85% of the standard rate, now receive $11.67 an hour.

This outcome stems from a citizen-led petition initiative in 2018 that sought to raise the minimum wage to $15 and eliminate tipped wages entirely. Lawmakers adopted the measure but then quickly amended it, triggering a multi-year court battle. In 2024, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that the Legislature had violated the state constitution by amending the initiated legislation in the same two-year term, ordering the original wage and sick leave increases. This decision sparked intense lobbying from the Michigan Restaurant and Lodging Association, which warned of “catastrophe” for the industry.

Ultimately, Governor Gretchen Whitmer and lawmakers struck a bipartisan compromise in February 2025. This agreement accelerated planned minimum wage increases but preserved the sub-minimum wage for tipped workers, avoiding its court-ordered phase-out. Justin Winslow, president and CEO of the Michigan Restaurant and Lodging Association, noted the challenges for businesses, particularly restaurants, which are “trying to find ways to shrink the total labor force to make the numbers work” amid decreased foot traffic and rising menu prices, as reported by Bridge Michigan. Conversely, Steven Dyme, co-founder of Flowers for Dreams, argued that “it’s about time” for wages to increase, emphasizing that “profits can’t be continuing to increase… without workers getting a larger share.”

A National Snapshot: Varied Progress and Federal Stagnation

Beyond Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Michigan, the minimum wage landscape across the U.S. in 2026 is a mixed bag of progress. Most New England states saw increases: Connecticut’s minimum wage rose to $16.94, Maine’s to $15.10, Rhode Island’s to $16, and Vermont’s to $14.42. However, New Hampshire remains an outlier in the region, adhering to the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour.

The federal minimum wage itself has been frozen at $7.25 since 2009. This 16-year stagnation means that in 20 states, including neighboring Pennsylvania, workers are still paid no more than this amount. The purchasing power of these wages has been severely eroded by inflation over the past decade and a half, leaving millions of workers struggling to afford basic necessities. This stark contrast highlights the growing disparity between states that have taken action to address economic realities and the federal government’s inaction on the issue, a point often emphasized by organizations like Business for a Fair Minimum Wage.

The Broader Cost-of-Living Challenge: Social Security’s Parallel Struggle

While minimum wage debates focus on hourly workers, the broader challenge of maintaining purchasing power extends to other income streams, notably Social Security benefits. For 2026, the Social Security Administration implemented a 2.8% cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), increasing the average retiree’s monthly benefit by approximately $55, from $1,959 to about $2,013. This marks the fifth consecutive year of increases, though it’s only slightly above last year’s 2.5% bump, according to AOL News.

Calculated using the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), the COLA aims to help benefits keep pace with inflation. However, critics argue that the CPI-W doesn’t accurately reflect the spending habits of older Americans, who often face higher medical and housing costs. Kevin Thompson, a certified financial planner, noted, “The COLA will not be material enough to offset the rising cost of health care, medicine or the overall cost of living, given that prices have increased so much.” The Senior Citizens League estimates that Social Security benefits have lost 20% of their buying power since 2010.

Adding to the challenge, rising Medicare Part B premiums directly chip away at these increases. For 2026, the standard Part B premium jumped to $202.90 a month, up from $185 in 2025, an increase of $17.90 that can vary by income. As Eric Croak, CFP, explained, “If the Medicare Part B premium increases by $15 or $20 per month in 2026, your raise is almost spent, and you are back to the same place you were before your raise, before you can buy your first meal with it.” This erosion of benefits underscores a parallel struggle to the minimum wage debate: whether any adjustments, be they for hourly workers or retirees, truly provide enough to maintain a reasonable standard of living in an economy defined by persistent cost increases.

Strategies to Navigate Economic Pressures

With both minimum wage workers and retirees facing significant economic headwinds, strategies to maximize income and maintain purchasing power are more critical than ever. For those planning for or currently receiving Social Security, options like delaying claims until age 70 can significantly boost monthly benefits, as COLAs are percentage-based and yield larger increases on higher base amounts. Continuing to work, even part-time, can also replace lower-earning years in one’s benefit calculation, though earning limits apply before full retirement age. Married couples can strategically coordinate claiming benefits to maximize household income. Furthermore, understanding how benefits are taxed and planning for Medicare costs are crucial steps to preserving financial stability.

On the minimum wage front, the varied state-level actions mean that workers’ economic fortunes depend heavily on their geographic location. Advocacy groups continue to push for federal action, arguing that a national minimum wage increase is long overdue to provide a consistent safety net across the country. Businesses, meanwhile, grapple with balancing increased labor costs with consumer demand and overall economic health, often seeking innovative solutions to maintain profitability while supporting their workforce.

The year 2026 vividly illustrates the fragmented nature of economic policy in the United States, particularly concerning baseline income. While individual states like New Jersey and Michigan have made strides, often through hard-won legislative battles or automatic indexing, the federal minimum wage remains frozen in time, creating vast disparities. This patchwork approach, coupled with the ongoing erosion of purchasing power for Social Security recipients, reveals a systemic challenge: the mechanisms in place to ensure a basic standard of living are struggling to keep pace with modern economic realities, leaving many to question the adequacy of current adjustments against the relentless march of inflation.