Quick Read

- His Dark Materials and The Book of Dust have sold over 49 million copies worldwide and been translated into 40 languages.

- Pullman’s work is renowned for its nuanced exploration of religion, authority, and the transition from youth to adulthood.

- Adaptations include film, BBC/HBO series, and theater, but the books remain most powerful on the page.

- The saga concludes with The Rose Field, marking the end of Lyra Silvertongue’s journey.

- Pullman champions storytelling as a vital means of understanding humanity and confronting dogma.

Thirty years ago, Philip Pullman introduced readers to Lyra Silvertongue and a universe where fantasy was a vehicle for realism, not an escape from it. Today, as the saga concludes with The Rose Field, Pullman’s impact is clearer than ever—not just in bookshops or on screen, but in the hearts and minds of millions.

There’s a bench in Oxford’s Botanic Garden, marked with names like “Lyra + Will” and overlooked by statues of daemons Pantalaimon and Kirjava. It’s a pilgrimage site for fans, a physical reminder of the emotional journey at the heart of His Dark Materials. This series, which began with Northern Lights (The Golden Compass in the US), has become a literary touchstone, adapted into film, theater, and television, inspiring everything from baby names to university lectures (The Guardian, news.ssbcrack.com).

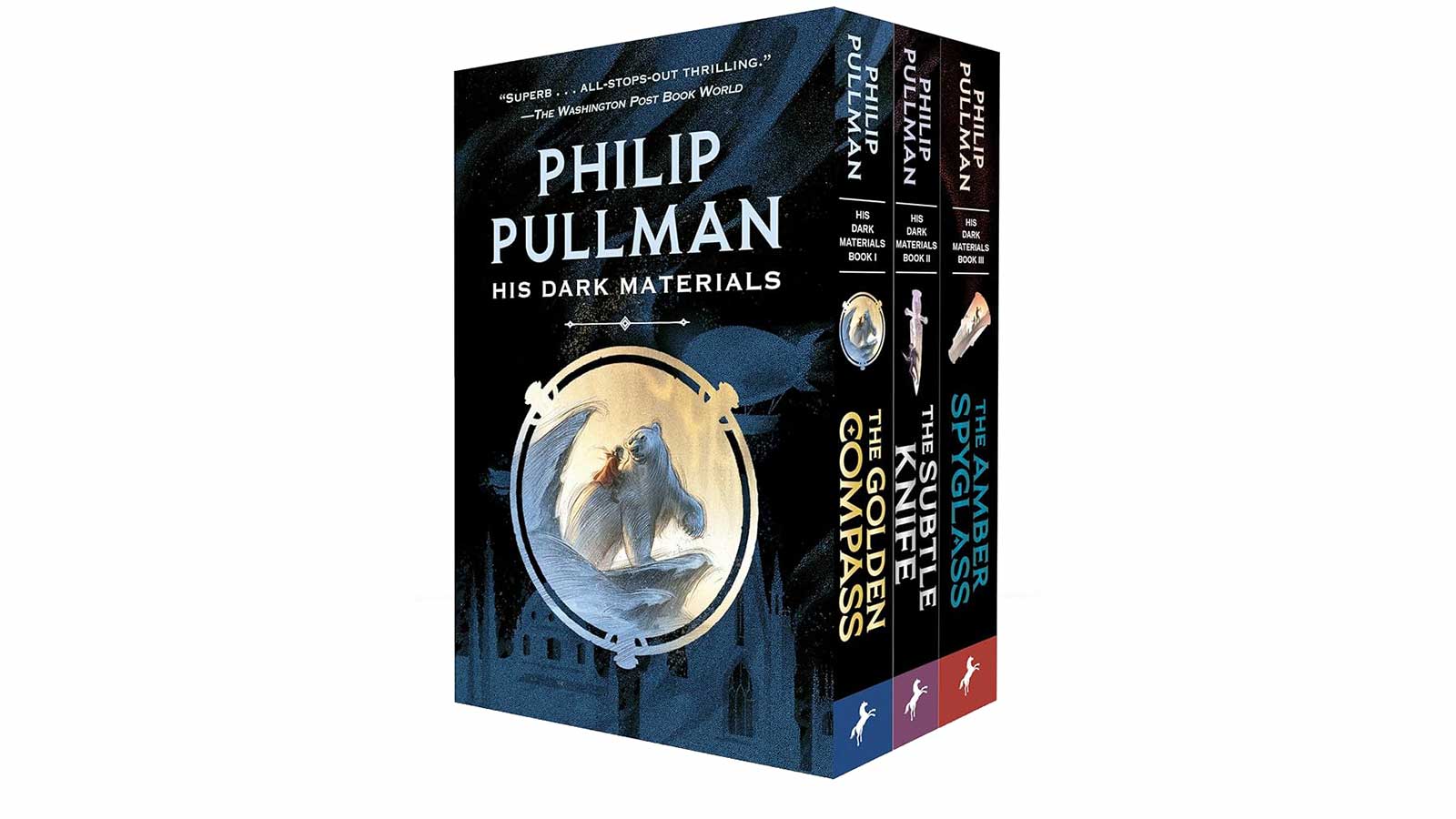

But Pullman’s achievement is more than cultural ubiquity. The original trilogy and its sequel, The Book of Dust, have sold over 49 million copies and been translated into 40 languages, yet they resist the franchise formula. Unlike Harry Potter or Game of Thrones, Lyra’s world remains most vivid on the page, perhaps because Pullman never sought to build a fantasy for fantasy’s sake. Instead, he set out to use daemons, armored bears, and angels to probe what’s true and vital about growing up, living, and dying.

At the core of Pullman’s work is a deep engagement with fundamental questions: What does it mean to be human? How do we navigate the transition from innocence to experience? The journey of Lyra, a 12-year-old girl who crosses worlds to rescue a friend and ultimately confront the mysteries of the universe, is as much about inner transformation as external adventure. Her battles with the Magisterium—an authoritarian religious order—mirror struggles against tyranny and misinformation in the real world.

Pullman’s relationship with religion is famously complex. He’s been called “the anti-CS Lewis,” critiquing the Narnia series for its religious allegory and views on women, and facing censorship campaigns led by religious groups. Yet he resists easy labels, describing himself as an agnostic who values the beauty and depth of religious traditions. In interviews with the BBC and The Guardian, he’s spoken of his admiration for the original impulses of religious figures, and his belief that religious questions—about origins, meaning, and evil—are among the biggest we face.

This ambivalence is reflected in his fiction. While His Dark Materials is critical of dogma and authoritarianism, it also celebrates curiosity, imagination, and the spirit of free inquiry. The second trilogy, The Book of Dust, brings more nuance: nuns play heroic roles, and Lyra herself struggles with the seductions of rationalism, risking her relationship with her daemon and her own sense of wonder. Pullman warns against both religious absolutism and the cold skepticism that denies meaning and magic. As Lev Grossman wrote in The Atlantic, Pullman adds to his religious skepticism a skepticism about skepticism itself.

His stories are built on metaphors that resonate deeply. Daemons, animal companions that represent aspects of identity, stand in for the inner voices that guide—or mislead—us. Dust, the invisible particles associated with consciousness, becomes a symbol for self-awareness and the complexity of growing up. The alethiometer, or golden compass, is both a device for truth and an emblem of creative flow.

Pullman’s refusal to categorize his books as simply “children’s literature” is justified by their scope. They investigate morality, sexuality, science, and the importance of storytelling without sacrificing adventure or accessibility. As Katherine Rundell told The New York Times, “The books understand that children crave stories on the epic scale, that infinity is not too large for them.” Pullman’s work never underestimates its audience, inviting readers—young and old—to wrestle with the biggest questions and to find their own answers.

Throughout his career, Pullman has emphasized the ethical responsibility of fiction. In a 2005 lecture, he argued that stories help us learn what’s good and bad, generous and selfish, cruel and kind. This commitment to storytelling as nourishment for the soul is perhaps his greatest legacy. He’s shaped Lyra’s world with care, never letting spectacle eclipse substance.

Even as his novels have inspired adaptations and cultural phenomena, Pullman’s universe remains resistant to commodification. Attempts to translate his books to screen have often struggled to capture the philosophical richness and emotional subtlety of the originals. Perhaps that’s because, as Pullman himself observed, fantasy is a great vehicle when it serves realism, but “a lot of old cobblers when it doesn’t.”

What endures, then, is not just the adventure or the magic, but the invitation to question, to imagine, and to grow. Pullman’s novels offer a framework for understanding the world—reminding us that, visible or not, we all carry something like daemons, and that our journey toward knowledge is both a challenge and a celebration.

In the final reckoning, Philip Pullman’s legacy is not as a provocateur or a builder of worlds, but as a champion of curiosity and compassion. By daring to confront dogma, celebrate storytelling, and honor the complexity of belief, he has expanded the boundaries of fantasy—and, perhaps, helped us see our own world more clearly.

Sources: The Guardian, news.ssbcrack.com