Quick Read

- Taylor Swift’s ‘Father Figure’ uses interpolation, not sampling or covering, of George Michael’s 1987 hit.

- Swift’s lyrics explore mentorship, exploitation, and her fight for ownership of her music.

- The song is written from the perspective of the record executive who first signed Swift.

- Interpolation allows artists to honor original songwriters while asserting creative control.

- Swift’s battle over her master recordings is central to the song’s meaning.

Understanding Interpolation: More Than a Cover

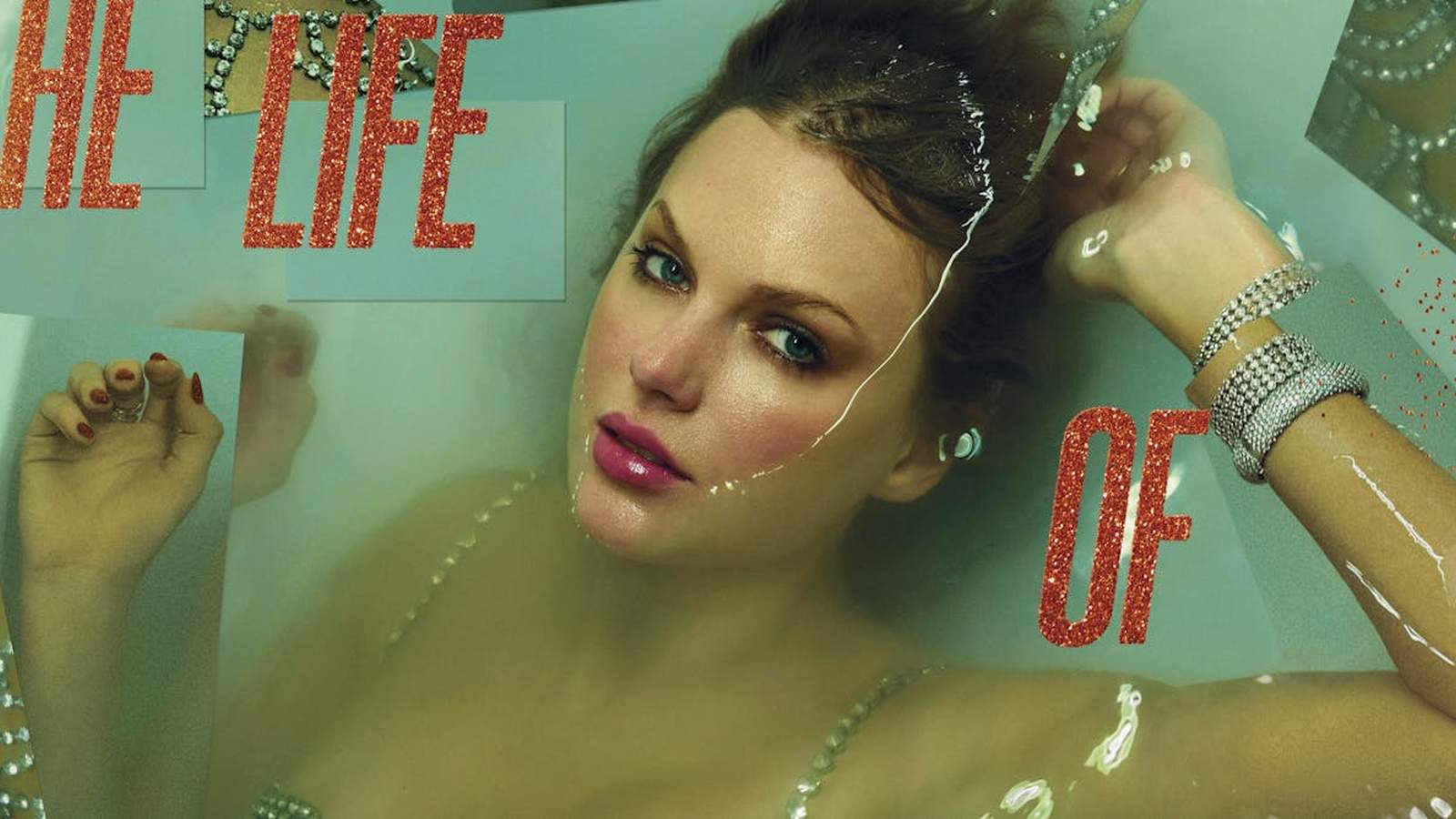

Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Life of a Showgirl, draws listeners into a world where music’s past and present collide. Track four, “Father Figure,” stands out—not just for its haunting melody, but for the way it reimagines George Michael’s iconic 1987 hit. While Michael is credited as a songwriter on Swift’s version, this is not a simple cover. It’s an interpolation—a term that’s become increasingly relevant in modern pop music. But what exactly does interpolation mean, and why is it the chosen method for Swift’s creative tribute?

In popular music, the lines between covers, samples, remixes, and interpolations can blur. A cover is a new performance of an existing song, a tradition as old as the recording industry itself. Sampling, by contrast, means directly lifting a segment of an existing recording—say, a guitar riff or vocal phrase—into a new track. Remixes manipulate the original audio, reshaping its structure or mood. Interpolation, however, is something different. Instead of borrowing the original recording, artists re-perform a recognizable element—melody, lyrics, or riff—within a fresh composition. The result is both familiar and new, a conversation between generations of songwriters (The Conversation).

For “Father Figure,” Swift doesn’t reuse Michael’s recording, but she echoes his chorus—“I’ll be your father figure”—and crafts a melody reminiscent of his. These subtle references pay homage to the past while establishing the song as a distinct work. In the eyes of copyright law, this matters. Interpolation requires permission from the original songwriters, but not the owners of the master recording. This legal nuance has made interpolation an attractive tool for today’s artists, allowing them to honor musical history while avoiding the costly “double clearance” of sampling.

Lyrics as Legacy: Power Dynamics and Personal Struggle

But “Father Figure” is much more than an exercise in songwriting technique. The lyrics unfold a story that’s both personal and universal—a tale of mentorship, ambition, and the price of loyalty in the music business. Swift writes from the perspective of the record executive who first signed her, widely understood to be Scott Borchetta, former CEO of Big Machine Records. Through his eyes, she explores the complicated dance between nurturing talent and exploiting it.

The opening verse sets the stage: “When I found you, you were young, wayward, lost in the cold / Pulled up to you in the Jag’, turned your rags into gold.” The executive is the benefactor, the gatekeeper to success, but his generosity comes with strings attached. The chorus sharpens the power dynamic: “I’ll be your father figure / I drink that brown liquor / I can make deals with the devil because my dick’s bigger / This love is pure profit.” Swift lays bare the transactional nature of the relationship, where mentorship is a mask for commercial interests (Elle).

The second verse deepens the tension: “They want to see you rise, they don’t want you to reign / I showed you all the tricks of the trade / All I ask is for your loyalty / My dear protégé.” Loyalty is demanded, not earned. The bridge and final chorus evoke the fallout as Swift parts ways with her mentor: “You want a fight, you found it / I got the place surrounded / You’ll be sleeping with the fishes before you know you’re drowning.” The battle over ownership, especially of Swift’s masters, becomes a metaphorical war. The executive’s voice is equal parts threat and lament, reflecting the real-life struggle Swift faced when her master recordings were sold to Scooter Braun—a saga she detailed in a heartfelt open letter in 2019.

Industry Reflection: Exploitation and Empowerment

“Father Figure” isn’t just about Swift’s story. It’s a warning to other young artists who enter the industry with dreams and trust, often at the mercy of those who see music as “pure profit.” The song interrogates the very nature of mentorship in entertainment—a world where guidance often comes at a price, and creative control is fiercely contested.

Swift’s decision to interpolate George Michael’s song, rather than simply cover it, is itself a statement about agency. By re-recording and reframing the narrative, she asserts ownership not only over her music but over her story. The act of interpolation is a creative maneuver and a legal strategy—a way to honor influence without relinquishing control. Other artists have followed similar paths. Ariana Grande’s “7 Rings” and Beyoncé’s “Energy” both interpolate classic songs, crediting original writers while forging new ground. In each case, interpolation serves as a bridge between eras, allowing artists to converse with the past while shaping the future (The Conversation).

The song’s lyrics are also a study in shifting perspectives. Swift has long been known for her ability to write from the vantage point of others, whether lovers, rivals, or industry figures. Here, she steps into the shoes of the executive, revealing the seduction and danger of being a “father figure.” The refrain “Leave it with me / I protect the family” is both a promise and a warning—a reminder that protection often comes with a hidden cost.

Cultural Capital: The New Value of Interpolation

Historically, covers were seen as derivative—marketable but lacking in originality. Interpolations, on the other hand, carry higher cultural capital. They represent a dialogue, not a reproduction. As music scholar Roy Shuker notes, covers are often dismissed, even when they reinvent the material. Interpolations invite listeners to engage with both the old and the new, to appreciate the artistry in transformation (Cosmopolitan).

For Swift, an artist celebrated for her creative agency, the choice to interpolate is deeply meaningful. It’s a way of reclaiming her narrative, of speaking to her own experience in the industry, while inviting listeners to reflect on the power structures that shape all artists’ careers. The song’s final lines—“You know, you remind me of a younger me / I saw potential”—echo the bittersweet recognition of legacy. The mentor sees himself in the protégé, but the cycle of ambition and betrayal continues.

“Father Figure” is already sparking debate among fans and critics. Some speculate it could be about a rival singer, but the most convincing theories point back to Swift’s own journey—her battles for ownership, her complicated relationships with those who claimed to protect her, and her ultimate triumph in buying back her masters. The song is both a personal reckoning and a universal commentary on the price of success in a business built on dreams and deals.

Swift’s “Father Figure” stands as a testament to how modern artists can wield musical history and legal nuance to tell stories that resonate far beyond their own careers. By choosing interpolation, she not only honors George Michael’s legacy but reframes her own, challenging the industry’s power dynamics and inspiring a new generation to demand creative control.