Quick Read

- John Roberts began shaping U.S. voting rights policy as a young lawyer in the Reagan Justice Department.

- His strategies focused on limiting the Voting Rights Act’s reach, favoring an ‘intent’ standard over ‘effects.’

- Roberts’s influence continues as Chief Justice, notably in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision and the 2025 Louisiana v. Callais case.

- The Supreme Court’s current conservative majority may further restrict VRA protections, impacting minority voters nationwide.

Roberts’s Early Crusade: A Young Architect in Washington

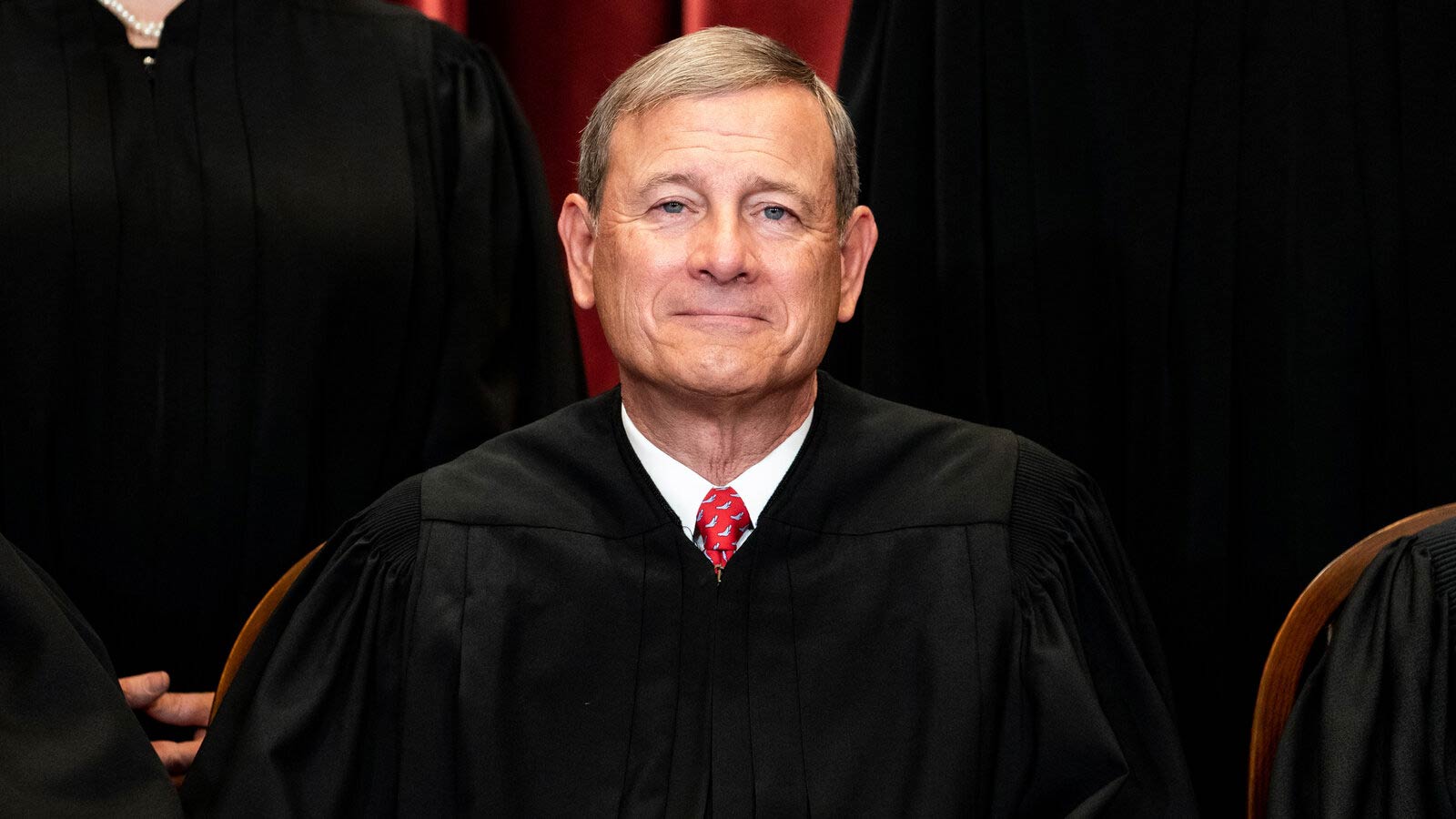

Long before John Roberts became Chief Justice of the United States, he was a young lawyer with a mission: to reshape the Voting Rights Act (VRA). In the early 1980s, Roberts was a rising star in the Reagan Justice Department, handed the crucial voting rights portfolio at a time when the fate of minority voter protections hung in the balance. His fingerprints are all over the strategies and arguments that would echo for decades, culminating in today’s Supreme Court debates.

The battleground was Section 2 of the VRA—whether it should protect against election laws with a discriminatory effect, or only those passed with clear discriminatory intent. This distinction was no mere technicality; it determined whether civil rights groups could challenge voting rules that, while not overtly racist, effectively suppressed minority votes. Roberts, alongside other ideological conservatives, fought to preserve the “intent” standard, making it nearly impossible for plaintiffs to succeed. As The Atlantic details, Roberts produced a steady stream of memos, talking points, and op-eds, shaping the administration’s public messaging and internal arguments.

The 1982 Showdown: Politics, Strategy, and the Limits of Reform

Reagan’s White House initially leaned toward compromise, hoping to avoid a messy public fight over a popular law. Civil rights advocates, however, demanded stronger protections and a clear “effects” standard. Roberts was the administration’s intellectual engine, scripting responses for congressional testimony and crafting arguments that would later resurface in Supreme Court opinions.

His approach was tactical and, at times, combative. Roberts dismissed the evidence presented by civil rights leaders, insisting that circumstantial evidence could prove intent and arguing that an “effects” test would unleash endless litigation and impose quota systems in elections—a claim echoed in presidential statements almost verbatim from Roberts’s memos.

Yet, the political winds shifted. Republican Senator Bob Dole, determined to preserve his party’s legacy on civil rights, brokered a deal: Section 2 would be amended to include the “effects” standard. Roberts and his allies, finding themselves outmaneuvered, were forced to watch as the reauthorization passed with overwhelming bipartisan support.

From the Halls of Congress to the Bench: Roberts’s Enduring Vision

The defeat in Congress did not end the conservative campaign against the VRA. Instead, it shifted the battlefield to the judiciary. The founding of the Federalist Society in 1982 marked the beginning of a new strategy: if you want to change the law, change the judges. Over the next two decades, Roberts and other conservative legal minds ascended to positions of immense power, culminating in Roberts’s appointment as Chief Justice.

As the Supreme Court’s leader, Roberts continued the project he began as a young lawyer. In 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder, he authored the opinion that effectively gutted Section 5, freezing the formula that required certain states to seek federal approval before changing election laws. This move, echoing his earlier arguments, weakened federal oversight and opened the door for states to enact new voting restrictions.

The 2025 Crossroads: Louisiana v. Callais and the Future of Voting Rights

Now, in 2025, the Supreme Court faces a momentous case: Louisiana v. Callais. At stake is whether states can use race data in redistricting—a decision that could eliminate Section 2 protections for minority voters. During oral arguments, a majority of conservative justices, including Roberts, appeared receptive to forbidding any use of racial data, potentially allowing states to redraw districts in ways that would dilute minority voting power, particularly in the South.

The echoes of Roberts’s 1980s memos resound in the courtroom. The central debate—intent versus effect—is the same one Roberts engineered decades ago. He is no longer a junior staffer but the chief arbiter, with the power to shape the law not through political compromise but judicial decree.

Legacy and Controversy: The Human Cost of Legal Strategy

Roberts has always insisted that his positions are rooted in principle, not politics. He claims to oppose quotas in elections just as in employment and education, framing his arguments as a defense of democratic values. Yet critics argue that his vision has systematically eroded protections for minority voters, making it harder to challenge discriminatory practices and easier for states to manipulate electoral maps.

Documents from the National Archives reveal a man deeply committed to his cause, willing to marshal every rhetorical and procedural tool to advance his agenda. Roberts’s work was not just technical legal advice—it was a sustained campaign to redefine the very meaning of voting rights in America.

As the Court prepares to rule in Louisiana v. Callais, the stakes could hardly be higher. The outcome may determine whether the Voting Rights Act remains a robust shield for minority voters, or a hollow relic of past struggles.

Chief Justice Roberts’s decades-long project to reshape the Voting Rights Act highlights how individual conviction and strategic persistence can alter the course of American democracy. His story is a reminder that legal battles are rarely just about statutes—they are about who gets to participate in the fundamental act of choosing leaders. As 2025’s Supreme Court decision looms, the nation must reckon with the real-world consequences of decades of legal maneuvering, and whether the protections forged in the crucible of civil rights will endure or fade into history.